Managing Logistics During COVID-19: Lessons Learned in Hawaii County

Emergency managers know they will respond to a variety of incidents. This includes both natural and man-made disasters, such as earthquakes, hurricanes, terrorism, and public health threats, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Hawaii’s reality is no different. Prior to the pandemic’s presumptive impacts, the Hawaii County Civil Defense Agency (hereafter known as the “Agency”) activated its emergency operations center in January 2020. In an instant, we were thrust into this unprecedented global contagion.

As the Agency’s logistics section chief, I will share the top three logistics lessons I learned, which created previously unrealized operational efficiencies. First, streamlined operations required a centralized purchasing, supply and distribution center. Second, proper inventory accountability called for a comprehensive inventory management system. Finally, for future mitigation, the County needs a strategic stockpile. Let me frame these lessons by first providing geographical and political context.

Context: Hawaii County

The Agency consists of a six-person team responsible for the 4,028 square miles of Hawaii Island, nearly 75% the geographic size of the state of Connecticut. The 200,000-person population is ethnically diverse: 34% Caucasian, 29% multi-racial, 22% Asian, and 12% Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander. The Hawaii government structure is inimitable, as the “County” is the only subordinate jurisdiction.

The governor oversees the four mayors of Hawaii County, Maui County (which includes Maui, Lanai and Molokai Islands), the City and County of Honolulu (Oahu Island), and Kauai County. With no other municipalities, all local government functions operate within the county. This has broad implications about each county’s oversight of its communities, residents and visitors. This fundamental understanding allows us to unpack the most significant logistics lessons learned during COVID-19.

Lesson 1: Centralized Purchasing, Supply and Distribution

Providing service to County departments required a centralized purchasing, supply and distribution platform. I first needed to identify our team, which included managers in the finance department. From here, we surveyed all county departments to assess product demand, like personal protective equipment (PPE). The finance team then conducted vigorous research, immediately procuring supplies based on current and projected demand.

We certainly experienced challenges. Well before COVID-19 was declared a pandemic in mid-March, the global supply chain was extremely stressed. The world was competing for product, making acquisition difficult. Unsurprisingly, we received solicitations from third-party sellers, promising PPE availability and ship-times. Prices and minimum purchase quantities, however, were generally higher than through known vendors. Additionally, many items did not meet any certification standard, such as through the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). We paused to consider a broader strategy that included brand reputation analysis and standards conformity.

To mitigate these challenges, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published myriad documents to help local jurisdictions identify solutions, such as understanding how to optimize and extend the use of existing PPE. These publications allowed for immediate acquisition of vetted products, such as alternatives to the dwindling supply of N95 respirators.

After establishing centralized purchasing, we identified a single supply and distribution location. This was to ensure that all County departments would promptly receive their requested supplies. A natural point-of-distribution was the Agency’s 10,500 square-foot warehouse. I rearranged the durable equipment, dedicating 25% of my storage capacity to consumables. Though our strategies and tactics evolved, the vision of centralized supply and distribution remained clear.

Completely executing this vision, however, required additional manpower. We enlisted 14 Hawaii National Guardsmen to assist, who performed vital work in two areas: comprehensive warehouse reorganization and an independent inventory audit. Both tasks were necessary to ensure we were operating an optimally efficient fulfillment center.

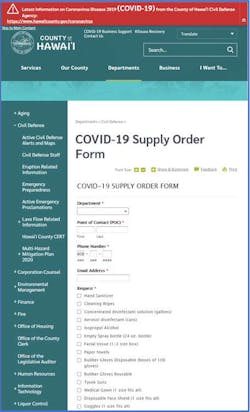

Even though my warehouse conceptually supported seamless distribution, we still experienced debilitating inefficiencies. After brief introspection, I realized I was poorly managing the ordering process. I haphazardly gathered departmental requests through multiple channels: e-mails, texts, phone calls and in-person conversations. After contemplating possible solutions, I asked the County IT Director to create an online ordering system. Her team then devised a web-based order form (Figure 1), which contained all likely combinations of items and unit sizes. The form integrated seamlessly with our County e-mail platform, where I created an automatic reply template using embedded functions. By eliminating multiple channels, we reallocated 20% of our time to other critical functions, such as actually fulfilling orders.

Though this centralized system streamlined our logistics operations, a judicious logistician must continue to ascertain weaknesses. To that end, proper inventory accountability was our next task.

Lesson 2: Inventory Management

What naturally followed the centralized purchasing, supply and distribution center was proper inventory management. Since massive amounts of consumable inventory were moving to and from the Agency’s warehouse, we needed to comprehensively capture each transaction.

After multiple iterations, we developed an optimally efficient inventory management system.

The first two versions were exclusively Excel-based. My past work experience, graduate school coursework, and the fact that Excel already existed on the County IT network made this choice ideal. Modest, the first version consisted of a dashboard and individual spreadsheets for each item. Using basic formulas, I linked the total quantity of each item with the dashboard, which allowed for clear and concise reports. However, spreadsheet maintenance was problematic. Foremost, I failed to distill each item by unit size, making for continuous manual calculations so that records reflected actualized stock. Additionally, since each item on the dashboard was linked to its own spreadsheet, I was managing superfluous individual spreadsheets. This proved to be mentally laborious and unsustainable.

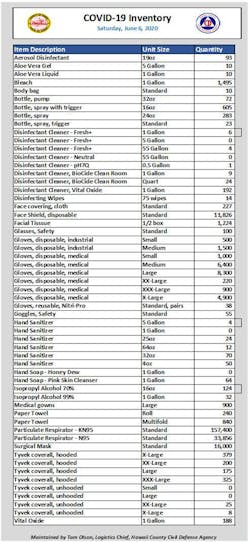

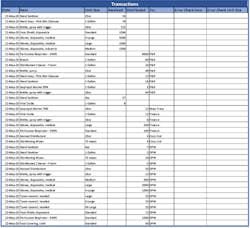

Though the second iteration simplified how transactions were recorded, this required advanced formulas. After receiving assistance from my graduate school network, we came up with a robust, yet simple model. This version required only two spreadsheets: the first was a standard dashboard (see Figure 2), while the second listed each transaction (Figure 3). It also contained “error check” functions, which ensured complete transaction accuracy.

Though maintaining this system was remarkably easier, it was operationally challenging.

The file responded slowly to even the most basic functions, as it contained numerous interdependent formulas. Slow response time equated to more time spent on records management and less time spent in tangible support. Furthermore, with complex formulas, it would be difficult to replicate for future incidents. We were at yet another junction point.

The third iteration was an inventory management software to which the Agency already subscribed. Regretfully, I invested little into understanding this tool. In seeking continuous improvement, I spent more time with the program. After initial exploration, I identified its bountiful strengths. First, assigning items to personnel was remarkably simple after constructing each of the 1,800 unique items and 50 departmental points of contact. Second, the system could generate numerous reports that could be provided to supervisors immediately. Though I have yet to discover the totality of this software, implementing this system greatly enhanced our operations. This allowed us to focus on a broader mitigation strategy, as outlined in the next section.

Lesson 3: Strategic County Stockpile

Though we attempted to properly forecast the county’s demands, we were behind the supply curve from the onset. Comprehensively understanding the strained supply chain led us to consider having a perpetual and codified stock of consumable items. Although supplies might be available from outside sources, we were careful not to construct a strategy that relied on the external. This mitigation measure called for the creation of a strategic county stockpile.

Like the Strategic National Stockpile, the county stockpile would supplement normal on-hand supplies. Possessing an all-hazards approach, it would include particulate respirators, rubber gloves and hand sanitizer. Though exact items and minimum required quantities have not yet been identified, average burn rates can inform estimates. The maintenance strategy includes cycling out supplies prior to expiration. For example, N95 particulate respirators could be given to the public works department before shelf-life expiration. This strategy would ensure that items are current and functional.

Looking Forward

During the initial months of COVID-19, our team was able to rapidly adapt to the dynamic environment to deliver much needed supplies in a timely manner. The lessons of centralized purchasing, supply and distribution, inventory management, and a strategic stockpile will significantly alter how Hawaii County manages future incidents.

Actualizing a centralized purchasing, supply and distribution center was most helpful after understanding that each individual County department shared common needs. This allowed our team to order bulk quantities, realizing reduced costs and ship times. Then, the ideal inventory management system that fit our jurisdiction’s reality allowed us to make modifications based on established county requirements. Finally, formally establishing a strategic stockpile has the profound potential for future operations, especially during periods of weak or fragmented supply chains.

All these lessons were made possible through the vast network of incredibly talented members of our team. This includes the senior-most levels of county leadership, the county finance and IT staff, and those individuals outside of the county network who were willing to impart their knowledge and skills to this critical mission.

In any emergency, there is unparalleled value in analyzing historical decisions to influence future actions. Though COVID-19 continues to be devastating, learning from this pandemic will inevitably make me, and hopefully readers of this article, more effective when disasters strike.

Thomas Olson is the logistics and finance staff officer for the Hawaii County Civil Defense Agency. A military veteran of the U.S. Coast Guard, his operational assignments included commanding the Coast Guard Cutter Chinook and serving overseas in the Arabian Gulf.

Reprinted with permission from the U.S. Coast Guard Academy Alumni Association’s The Bulletin magazine.

About the Author

Thomas Olson

Thomas Olson is the logistics and finance staff officer for the Hawaii County Civil Defense Agency. A military veteran of the U.S. Coast Guard, his operational assignments included commanding the Coast Guard Cutter Chinook and serving overseas in the Arabian Gulf.