Big pharma has a big material handling problem. Make that several. Criminals are infiltrating the nation’s pharmaceutical supply chain with knockoffs and diverting legitimate drugs to the black market. Although this is nothing new, the problem has worsened in recent years. Drug counterfeiters have become more sophisticated, and in the battle to protect public health, the wrong side is winning.

FDA criminal investigations of drug counterfeiting have increased six fold since 2000, and the U.S. pharmaceutical industry loses approximately $2 billion to counterfeiting every year, according to Ross Enterprise Inc., a subsidiary of CDC Software.

New York-based Center for Medicine in the Public Interest estimates sales of counterfeit drugs to reach $75 billion worldwide in 2010, an increase of more than 90% from 2005. As much as 10% of the current global medicine supply is counterfeit, according to the World Health Organization.

The long-term prognosis from the healthcare community is dire, and laws designed to put a tight lid on counterfeiting are getting tougher. The idea is to guard public safety, reduce crime and protect profits of legitimate pharmaceutical businesses.

Though the regulations are well intended and necessary, problems inevitably arise when the ‘who’ and ‘what’ are spelled out, while the ‘how’ is missing. That’s happening right now for companies that move pharmaceuticals in California.

State of the Industry

One of the most daunting regulatory challenges for any business involved in manufacturing or distributing pharmaceuticals is the requirement to track and trace individual drugs through pedigrees.

Drug pedigrees are not new, and they are not restricted to California. In 1988, the FDA enacted the Prescription Drug Marketing Act (PDMA), a key provision of which was the requirement for pedigrees—statements of origin that identify all prior sales of a specific drug and all transaction dates as well as the parties involved in each transaction. Under the PDMA, it’s the wholesaler’s responsibility to generate and maintain each drug pedigree and produce it, on demand, to an inspector or purchaser.

In recent years, though, regulations have become tougher, with state legislatures adding complexity to the national requirement. “More than 35 states have their own pedigree laws or are currently working on them,” says Brian Daleiden, director of product marketing at SupplyScape, a software supplier to pharmaceutical companies.

“Florida, California, Texas and Indiana are just a few examples,” adds David Crawford, project manager at supply chain consulting firm Tompkins Associates. “More states are expected to follow.”

California is taking the most aggressive approach by far with its new electronic pedigree regulation, set to take effect Jan. 1, 2009. The state will be the first in the nation to require electronic pedigrees initiated by manufacturers and verified and updated by every link in the pharmaceutical supply chain—from point of origin (manufacturer) to wholesale distributor to final dispenser (pharmacy). Because of fears of forgery, paper pedigrees will no longer be allowed in the Golden State.

Further complicating matters, the new regulation will require item-level serialization for visibility all the way down to a drug’s smallest saleable unit. This is an industry first. Layers upon layers of inventory complexity will be added to California’s pharmaceutical supply chain. “Changes are expected to be substantive for all wholesalers, resellers and redistributors of pharmaceuticals,” says Crawford.

Specifically, three main requirements of the new regulation— item-level serialization, more detailed data collection and electronic information management—will test the limits of pharmaceutical handling.

Needles in Haystacks

Most drugs today are not serialized at the item, case or pallet level, according to SupplyScape, and the software firm estimates it will take a minimum of five to 10 years for all drugs to be serialized at the item level.

Serialization introduces much more complexity into the process of managing inventory. Manufacturers must assign a unique number or identification code to each packaging unit. A typical serialization system includes a code to identify manufacturer, product type and specific item unit, SupplyScape explains in a recent white paper addressing the new requirements.

Although California puts the burden of creating the pedigree on the manufacturer, the new regulation isn’t just a manufacturer issue. It will undoubtedly have a domino effect throughout the industry.

Material handling processes—from picking to packing to shipping—will have to be reconfigured. Specifically, most experts agree that more process steps will be required. Crawford estimates the California regulation will result in a 10% overall increase in labor throughout the industry.

A pharmaceutical distributor, for example, will have to maintain tighter control of inventory, and that may require upgrading the WMS and rethinking picking strategies. “If there is any possibility that a given SKU/lot combination with different unique identifiers can enter a wholesaler’s distribution facility, then there is a regulatory requirement for having processes and procedures in place to keep the products segregated— physically as well as within any WMS,” says Crawford. “With serialization, you can’t cross over lot numbers. You have to find a way to break down shipments into lots and put them away separately. You have to pick the same item in the same lot number, so you cannot batch pick across lots. Pickto- light technology can help manage lot control, but you can’t keep two lots in the same location. There has to be some way of segregating lots.”

In addition to creating and maintaining a more complex inventory system, California manufacturers responsible for generating e-pedigrees may also have to rethink packaging strategies.

“If a case has 100 syringes,” Crawford explains, “those 100 syringes have to be serialized. If it will be for sale individually, each syringe has to be packaged separately. The state wants information available at the lowest level possible. It’s like a social security number for every sellable unit out there,” he adds.

Production lines may have to be converted from bulk to unit-of-use packaging. “Since each package has to have a unique identifier, bottles may have to be packaged separately,” says Daleiden. “Manufacturers have to decide where in the line is the best time to package and tag the items,” he adds. “Should they stock the items then identify them later before shipping?”

Jack Walsh, director of sales and brand protection solutions at Videojet Technologies, says manufacturers will need to have more control over product in process. How they achieve that is up to them.

“A company may need a custom conveyor in some instances for complete control of items on the packaging line,” says Walsh. “Another may create a multi-lane system that batches product for cases or split product in line and automatically batch it for operators in packaging. There isn’t a material handling product that is going to fit an infinite number of solutions,” he adds.

To cope with the additional complexity, some companies are using a “phase-in” approach by maintaining distinct inventory earmarked for California, says Daleiden. Of course, this strategy isn’t without its problems. They have to decide whether they are going to require serialized product upfront or find a way to segregate the California inventory from the rest as it comes in. Other companies are starting slow by tracking and tracing only “high-risk” drugs until they can get up to speed.

Selecting and implementing track-and-trace procedures for collecting, verifying, updating and storing new data for the e-pedigree mandate will be challenging for most companies.

Not only does data have to be collected, it must also be ‘read’ and verified by other links in the chain. The California law requires pharmacies and wholesalers to verify the authenticity and status of serial numbers generated by manufacturers.

“This means affirmatively verifying, before any distribution of a prescription drug occurs, that each transaction listed on the pedigree has actually occurred,” Crawford explains. “At the time of physical receiving,” he continues, “a process must be in place to confirm that the physical product being received has a matching pedigree.”

Though California does not mandate any specific track-and-trace technology, RFID appears to be the most promising, and the FDA has openly recommended it. The reasons for the FDA endorsement are clear: Shipment information can be built into an RFID tag and captured electronically by an RFID scanner. And, RFID allows for efficient item-level data capture because it doesn’t require line of sight; an RFID scanner can ‘read’ an entire case at once and collect data for every bottle in that case.

Still, RFID isn’t problem free. “While RFID holds tremendous potential as an anti-counterfeiting tool, technology immaturity, high costs, a fuzzy return-on-investment picture and requisite infrastructure and business operational changes have slowed the pace of deployment,” says SupplyScape in its white paper. “Both linear and 2D barcodes can provide serialized, item-level information,” SupplyScape contends, “but they must be read one at a time, take longer to read and require a direct line of sight.” Building an RFID infrastructure is a major undertaking, both financially and operationally, SupplyScape adds, while “barcodes are significantly less expensive.”

“Because of uncertainty about how fast their trade networks can build their RFID infrastructure, companies are looking at barcodes and even dual tagging,” Daleiden adds. That’s not to say generating e-pedigrees with barcodes will be any easier. “Tagging and scanning alone require significant infrastructure investments,” says Daleiden. “Manufacturers will have to label all the individual products, then scan them on the outbound side so that they know which drugs went out.”

Walsh agrees. “Compliance will require a combination of coding and labeling, marking, data capture and database management tools and software— the whole kit and caboodle.”

| Further Study… For more information about the complex material handling challenges that come with e-pedigree requirements, contact the following sources:

|

Speaking in Tongues

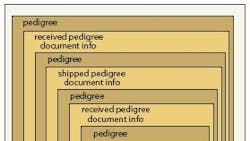

California defines an e-pedigree as an ever-growing chain of custody detailing a drug’s path through the supply chain, so each company involved in the manufacture or distribution of the drug has to view and add to the pedigree. Under the California scenario, the seller identifies the drug and the full chain of custody then certifies the pedigree and transmits it in advance to the trading partner receiving the drug, which then authenticates the pedigree. When the shipment arrives, the pedigree is matched to the product and signed, verifying its accuracy.

Data standards will be necessary to ensure every link can receive, interpret and process the same information. The GS1 EPCglobal drug pedigree messaging standard has been recognized as one approach to developing serial numbers, but that’s only a starting point.

Authentication, according to SupplyScape, “leverages the product serial number information stored on an RFID tag or barcode on a drug’s packaging so that it can be used by wholesalers and pharmacies to verify the product integrity of the drug package.”

“It’s one thing to serialize your product,” Daleiden says, “but if your downstream trading partners aren’t checking that information, you’re not really getting any benefit. You can’t do this in a silo.

“Once the product is tagged by the manufacturer, the wholesaler needs to receive the product, scan it, pick it and ship it to pharmacy chains,” explains Daleiden. “Dispensation points (pharmacies) need to receive the product, as well. There are more than 60,000 pharmacy dispensation points in the U.S. and 11,000 in California alone,” he adds. “A lot of companies are going to have to have the ability to scan an RFID tag.”

| Case Study #1 Is RFID the Answer? Cardinal Health, one of the “Big Three” pharmaceutical wholesalers in the U.S. next to AmeriSource-Bergen and McKesson, says industry standards and technology issues still need to be addressed by the healthcare industry before RFID can be adopted industry wide. According to the company, the industry must agree on a single RFID protocol and technology to avoid “significant process and cost inefficiencies.” Under California’s requirement, “serialized, item-level pedigrees will be the responsibility of the entire supply chain, starting with the manufacturer and ending with the pharmacy,” says Julie Kuhn, project director at Cardinal Health. “Furthermore, each company within the supply chain is responsible for ‘updating’ the item-level pedigree upon each change of ownership. No one throughout the chain can purchase a drug without a pedigree,” she adds. “While this has the potential to secure the nation’s supply chain, it also has the potential for massive red tape and onerous implementation.” Cardinal Health also has concerns about RFID read rates at all packaging levels and suggests the industry accept barcode technology in addition to RFID. Finally, unit-level “inference” should be accepted when unit-level read rates are not possible. Cardinal Health speaks from experience. From February 2006 through the fall of that year, the giant wholesaler tested ultra-high frequency (UHF) RFID tags to determine if they could be applied, encoded and read at normal product speeds during packaging and distribution. The company placed RFID tags on the labels of brandname, solid-dose prescription drugs then encoded the electronic product code (EPC) at the unit, case and pallet levels during the packaging process. The products were shipped from its headquarters facility in Dublin, Ohio, to its distribution center in Findlay, Ohio, where the data was read and authenticated as products were handled “under typical operating conditions,” according to the company. From the Findlay DC, the tagged product was sent to a pharmacy to test read rates and data flow using the same technology as the DC. Results from the pilot suggested that RFID tags could be inlaid into existing FDA-approved pharmaceutical label stock and applied and encoded on packaging lines at normal operational speeds. Cardinal Health also reported that the RFID tag application and encoding required “minimal adjustments” to its labeling and packaging lines. However, there were difficulties when it came to reading item-level data. Reliable unit-level read rates “in excess of 96%” were recorded when individual cases were scanned one at a time and when mixed with other products in tote containers ready for delivery to a pharmacy. On the other hand, unit-level read rates were not reliable within a full pallet load. Individual bottles were picked and placed in tote containers with other products that did not have RFID tags. While unit-level read rates from the totes were reliable during the quality-control phase, additional unit-level read rates were not reliable at the shipping dock of the distribution center or at the receiving doors at the pharmacy. Cardinal Health concluded that, while using UHF RFID technology at the unit, case and pallet levels is feasible for track and trace, several challenges remain before it can be adopted industry wide. Just months after the pilot results were announced, Cardinal Health said it would integrate RFID into the operations of its Sacramento, Calif., distribution center by the fall of 2007 to prepare for California’s e-pedigree regulation. “When manufacturers provide us with products containing item-level RFID tags, we’ll be able to ‘read’ the RFID tag when it enters our facility, and then, we’ll ‘read’ it again as it leaves our facility,” explains Kuhn. “We do not do any modification to the RFID tag. These are passive tags that are strictly a unique identifier,” she continues. “We use that unique identifier as a ‘key’ to pull or push required information for pedigrees to the pedigree application. The electronic signature that is utilized is the secured electronic transaction. So, we receive, read and pass the RFID tag through our DC, but we maintain and send the pedigree information electronically, not on the RFID tag.” |

| Case Study #2 Similar Challenges in Florida To create a Florida pedigree, API has to label incoming product with both lot number and date of receipt. When Florida first enacted the law, API wasn’t lot tracking, says King. He felt case-level serialization was the only realistic way to generate pedigrees without creating new storage locations. “We don’t have enough locations for every lot number of each day,” says King. “If lot number ABC comes in on Monday, and lot number ABC comes in on Tuesday, we have to be able to tell which day the product came in. And, that requires different locations unless you serialize cases.” If item serialization is mandated in Florida, as it will be in California, King will have to rework his inventory strategy again. Although the Florida regulation doesn’t require pedigrees to be electronic, King said receiving paper pedigrees from wholesalers and sending paper pedigrees to pharmacies every day “would be an administrative nightmare.” So, he chose the electronic route. API hit a wall, though, when the pharmacies it shipped to didn’t have the ability to decode and view API’s epedigrees. As a result, API considered an online solution from SupplyScape, a company that provides e-pedigree data management, authentication and digital certificate services. With the SupplyScape e-pedigree application, pharmacies simply go to an Internet browser to access a Web portal where they retrieve e-pedigrees for any drugs they purchase from API. Because SupplyScape’s e-pedigree data management software is hosted over the Internet, API was able to integrate it into its operations fairly quickly. The data is housed on SupplyScape’s servers, so API didn’t need to add data storage at its facility. API was also able to integrate the software with its WMS and process live pedigrees within 90 days, according to King. At receiving, API scans one-dimensional barcodes and builds a file on its WMS, which is connected to the SupplyScape application. The data file includes serial number, lot number, day received and PO number. At the outbound shipping dock, “we scan the serial number again, and that builds another file for SupplyScape that indicates to whom the product was sent,” King explains. Though regulatory compliance was the main goal, API experienced additional benefits as a result of case-level serialization and the e-pedigree application. The company now knows where the physical drug is located for any pedigree in its system. Physical product can be matched to pedigrees, making returns easier to handle. |

| E-Pedigrees, RFID Not Enough? Mikoh polled “several thousand” manufacturing and distribution managers in the pharmaceutical industry, and 67% reported they have experienced pharmaceutical tampering in the past. Fully 95% identified RFID as an “ideal solution” to protect product integrity during manufacturing and distribution. However, “an overwhelming 76% of respondents stated that RFID tags must be physically secure to safeguard against shrinkage, diversion and counterfeiting.” Mikoh concluded that “simple RFID is not enough to ensure pharmaceutical product integrity.” “While RFID is a promising solution, a hole must be addressed: physical security,” says Andrew Strauch, vice president of product marketing and management. Strauch says conventional RFID tags can be easily moved from one item to another without affecting RFID functionality. He adds that it would be easy for a criminal to remove the RFID tags, steal the drug and leave the tags in the empty carton. “Track-and-trace and e-pedigree systems detect the tag and infer the presence of the product. As a result, RFID can actually disguise theft and counterfeiting,” he says. To address this issue, Mikoh developed a line of RFID tags and labels called Smart&Secure that automatically become disabled if tampered with or moved. “The tag is a pressure-sensitive label incorporating a chip and antenna manufactured from destructible, conductive ink,” according to the company. “Its tamper layer causes antenna damage when the tag is compromised or removed.” Result: The RFID tag is disabled, and a tamper alert is automatically sent to an RFID reader. |