How Dimensional Weight Pricing Affects Material Handling Systems

FedEx and UPS made waves throughout the supply chain with the announcement of shipping rate updates that subject packages measuring less than three cubic feet to pricing based on dimensional weight. Before the update, carriers priced items smaller than three cubic feet based on actual weight and larger items based on actual size. This means e-commerce retailers could ship small items in large boxes filled with lightweight protective packaging for roughly the same price as smaller, denser boxes.

From the retailer's perspective, corrugate cases offer superior item protection and are easier for automated equipment to handle. However, from the carrier's perspective, reduced package density inefficiently uses cargo space and increases the cost per package. The dimensional weight (DIM) calculation enables carriers to better correlate the price charged for the shipment of an item with the space used on the delivery truck.

According to The Wall Street Journal, the new rate structure affects more than a third of all ground packages, the majority of which weigh less than five pounds. According to its 2014 service guide, FedEx calculates dimensional weight by multiplying the length by the width by the height (in inches) of each package, then dividing the total by a volumetric divisor, listed as 166 for domestic shipments. The final figure is then rounded up to produce the billable dimensional weight. UPS uses the same calculation.

The increased shipping rates leave e-commerce operations with a challenge to keep consumer shipping costs down in order to maintain high transactional volume. In a UPS survey of online shoppers, nearly 60% of respondents cited shipping costs as their leading cause of online shopping cart abandonment.

In order to prevent increased shipping costs from derailing orders, analysts expect e-commerce retailers to optimize packaging practices, shifting away from traditional corrugate cartons to more malleable packaging types that do not occupy as much excess space. E-commerce operations have myriad packaging options at their disposal, such as polybags, thin shipping envelopes and bubble packs. However, while each offers reduced overall package size and dimensional weight, they offer new challenges for material handling systems originally designed for more rigid packaging types.

The Challenges of Polybags

Some existing automation systems may be capable of handling polybags, but the advent of widespread DIM pricing and more small, direct-to-consumer orders means most e-commerce fulfillment centers face a larger volume of non-rigid packaging types than ever before. As distribution operations evolve from manual processes with isolated "islands of automation" to fully-integrated automated systems, companies establish performance benchmarks required to justify the automation investment. With polybags and other non-traditional packaging constituting a more significant portion of orders, fulfillment centers must decide if they want one automation system to handle all packaging types simultaneously or implement a separate system for polybags only.

The influx of flexible packaging types does not alter the throughput required to justify automation investments, and these new package-handling demands place a premium on gentle product handling and system flexibility. With multiple packaging types in use to optimize shipping price, the burden falls on material handling systems to accommodate increased packaging variety without compromising throughput, accuracy and product integrity.

Compared to traditional corrugate cases, malleable packaging types present several product-handling challenges. Polybags, for example, lack the structure to provide the same level of protection from impact as orders move through a distribution center. Many traditional material handling technologies were designed for items with firm, flat bottoms. However, polybag bottoms take the shape of the items contained within, creating potential for additional catch points from oversized bags. These handling challenges threaten product damage, shingling, jams, snags, irregular item and label orientation, and side-by-side products—all of which deter smooth travel from pack-out to shipping, risking unplanned downtime, increased order cycle times and worst of all, unhappy customers.

Can You Handle It?

Given the challenges involved with transitioning from full-case cartons to bagged and smaller items, operations can ask three questions to evaluate if a system can handle certain products:

1. Can existing technologies effectively handle the product?

The answer depends on the packaging type, the items within, the specifics of the existing technology and the desired throughput. For example, if an operation ships a cheese grater in a polybag, the system must be able to handle the shape of the cheese grater packaging, plus extra catch points that the polybag may present. OEMs can provide guidance on an existing system's capability to handle various product and packaging type combinations.

3. Can existing technologies identify the package contents?

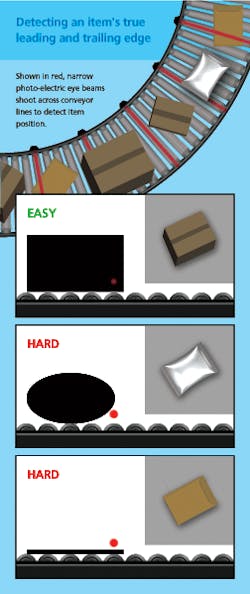

In addition to determining physical dimensions, material handling systems use scanning technology to identify a package's contents and intended route to its final destination. Polybags offer myriad scanning challenges. Their round shapes and non-flat surfaces produce reflective glare, encumber the process of presenting barcodes with the proper side up and present inconsistent scanning angles. Furthermore, without a rigid shape, bags complicate automatic label application and their inconsistent leading edges complicate triggering the scanning system at the proper time. Instead of a single narrow beam, an array sensor enhances polybag detection so that the scanner knows when to read a barcode.

Furthermore, additional scanners at opposing angles can improve scanning accuracy of uneven polybag surfaces to maintain successful identification rates.

Addressing the Challenge

Distribution operations can use or upgrade existing technologies to cope with the windfall of items in non-rigid packaging. Contrary to popular belief, some sliding shoe sorters are capable of handling polybagged items, provided the sorter has a well-designed conveying surface and pushing element. Upgrading a sliding shoe sorter from tubes to aluminum slats enables a wider variety of conveyable SKUs to pass through the system and provides a more continuous surface for improved polybag-handling performance.

Operations can also optimize conveyor system performance with strategic upgrades. In some cases, operations may need to upgrade zone sensors to better detect the true leading and trailing edge of items (see graphic, "Detecting an item's true leading and trailing edge"). Further upgrades include changing roller conveyors from three- or four-inch roller centers to two-inch centers and converting roller conveyor to belt conveyor or belted motor-driven roller zones. These upgrades provide a more consistent conveying surface, improving product flow and decreasing the risk of jams, improper orientation and side-by-side items.

Rather than relying on sophisticated accumulation conveyors throughout the warehouse, some carriers employ bulk handling to move parcels before advanced singulation systems separate items to a single-file flow before entering a sorter. As retailers and OEMs alike adjust to the proliferation of polybags, retailers may take cues from parcel carriers and incorporate more bulk flow in their fulfilment centers and only singulate when needed.

Tim Kraus is product management supervisor with Intelligrated, an automated material handling solutions provider.

--------------------

The Polybag Decision

In addition to automated material handling equipment, auxiliary systems in the warehouse can also affect lightweight, polybagged items.

The lesson? When planning for new items with challenging handling characteristics, look beyond automated equipment and consider the entire warehouse environment. Sometimes factors beyond the characteristics of the automated equipment dictate system limitations.