Autonomous Vehicles and Drones Are Coming — Is Your Supply Chain Ready?

The supply chain industry is becoming one of the most progressive adopters of new products, solutions and technologies. As an industry, we are creating radical innovations with augmented reality, virtual reality, advanced robotics, real-time inventory tracking, and exploring how 3-D printing could completely disrupt the supply chain in the next 10 years.

While many of these ideas still need quite a bit of research and development, most agree that both drones and automatic guided vehicles (AGVs) will play an increasingly important role in the supply chain in the not-too-distant future. But this will only happen if we are willing to take risks and make societal and business changes that allow innovation to flourish.

AGVs and Driverless Vehicles

Although AGVs and driverless vehicles have received much attention over the last year, AGV operations inside the warehouse certainly aren't new.

Driverless forklifts (Toyota), material moving robots (Kiva) and very narrow aisle trucks (Hyster) have been around for some time. These technologies have been rapidly advancing to the point where AGVs could soon be hitting the open road.

It's almost impossible to pick up an industry magazine or even the Wall Street Journal and not see regular AGV updates for new consumer and business solutions. This includes everything from Tesla's consumer grade Autopilot to new commercial driverless truck solutions from startups like Starsky Robotics, Drive.ai and Otto. Within the next five years, driverless vehicles on our nation's highways should be commonplace.

This is not just a quest to replace human workers with robotic solutions. The reality is our industry has been struggling to find drivers, and the shortage is expected to worsen. The trucking industry hauls 70% of the nation's freight—about 10.5 billion tons annually—and simply doesn't have enough drivers.

With tighter regulations governing allowable working hours for our driving workforce, companies are looking for alternative solutions.

In a recent article in the Wall Street Journal, Alex Rodrigues of San Francisco-based driverless truck startup Embark stated, "It's an industry that has clear need, where there is a substantial driver shortage—particularly of drivers that are experienced, safe and talented."

Last October, startup firm Otto (which had recently been acquired by Uber) successfully completed a fully automated delivery from a Budweiser brewery in Fort Collins, Colo., to its destination 120 miles away in Colorado Springs. This shows that solutions can be found to deal with on-road hazards such as construction zones, bad weather and erratic driving by other vehicles.

Here Come the Drones

Unlike AGVs, the use of drones in the supply chain is a very recent development, although their adoption in other industries, such as agriculture and photography, has been in place for years.

As of the beginning of 2017, few commercially available drone solutions specifically targeted at the supply chain industry were available, but almost every day we see vendors working on new solutions—many of which should be available later this year.

Our lab has been involved with two prototypes over the past 18 months. Working with yard management systems provider PINC Solutions, we have been testing an RFID scanning outdoor drone seamlessly integrated into a YMS. We have also been working with South African-based Dronescan and their approach to indoor cycle counting—extensively testing their manually-flown drone that scans barcodes inside a warehouse.

On a larger scale, one of the most anticipated and written-about use of drones in the supply chain is for last-mile delivery. In 2013, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos was interviewed on "60 Minutes" about the future of his company, and it was on this show that he predicted that in the very near future, 86% of all Amazon home deliveries would weigh less than five pounds. He followed this prediction with an announcement—that in the near future Amazon would achieve some of these deliveries using a new drone-based service called Prime Air. Three years later in December 2016, Amazon delivered on its promise with a home delivery in Cambridge, England.

While research suggests Amazon is leading the charge, a small California startup called Zipline has successfully piloted a major project in Rwanda where they claim to be delivering 40% of all blood needed for transfusions in hard-to-reach rural areas. Using a slingshot-launched fixed-wing drone, Zipline in ideal conditions can complete a 60-mile round-trip delivery of a package weighing up to 7 kg—delivered via parachute. Both Zipline flight operations and the end customer receive up-to-date information with real-time location and delivery estimates.

Other supply chain leaders are also creating their own prototype solutions. Automaker Mercedes has created a concept delivery van designed for urban areas called the Vision Van. The vehicle is a holistic system integrating numerous innovative technologies for final-stage delivery.

Each system includes a fully electric van, a delivery drone and advanced sorting/loading systems. Sophisticated routing and flight management systems handle every step of the process.

UPS, one the best-known last-mile delivery providers, is also developing drone solutions that augment the traditional delivery process. Earlier this year, the company tested a drone that launches from the top of a UPS package car, autonomously delivers a package to a residence and then returns to the vehicle, while the delivery driver continues along the route to make a separate delivery.

Technology, Innovation and Disruption

Digging deeper into researching drones, AGVs and other emerging technologies, you find that technology often moves forward at a pace much faster than the world it was designed to help.

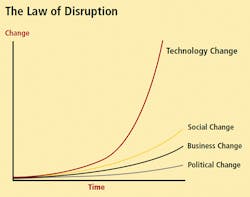

Look at the "Law of Disruption" chart (you could easily substitute the word "innovation" as it works either way). The idea is that technological progress often moves forward at a much faster pace than what societal tolerance, business ROI, or the political regulatory climate could ever dream about.

Business has traditionally been averse to drones because the ROI has been hard to calculate, costs associated with insurance coverage are uncertain, and OSHA and FAA regulations have been unclear. Finally, the political climate is often the most resistant to change.

It was only in August 2016 that Part 107 of the FAA Regulations—the guidelines that dictate the legal operation of drones outdoors—was released. Prior to this, companies were either operating under a special FAA exemption—or more commonly, operating illegally. Ironically, even with these guidelines, it is illegal for companies to engage in last-mile delivery at this time, because outdoor flight must take place within line-of-sight of an operator. Although exemptions may be possible, until the law is further clarified and developed, outdoor drone usage won't be widespread. That is one reason that Amazon's initial testing took place in England.

There are many other examples of where society, business and politics often stifle new solutions—whether it is AGVs on our highways or drones in our skies.

As our society becomes increasingly more risk-averse, we predict there is an increased chance companies will be reluctant to invest in new ideas if unpredictable obstacles prevent their adoption. Even so, our heritage has always been one that is consistently pushing the envelope of progress. We hope this continues.

Matt McLelland is research manager at Kenco Logistics Innovation Labs, a team of innovators working with customers to identify, research and prototype ideas and processes. The team also partners with entrepreneurs and vendors from multiple industries to identify trends that can be cost-effectively applied in the supply chain.