Last century, the normal strategy for solving productivity issues in the warehouse or distribution center was to throw bodies at it. Take an economy ranging anywhere from sluggish to moribund—coupled with skyrocketing costs for labor, fuel, materials and more—and you end up with organizations looking to automation and other forms of technology.

But there is more to using technology than simply removing human beings and inserting machines. Designing a true 21st Century warehouse, whether a greenfield build or a retrofit, requires a lot of thinking, pre-planning and testing. Following are five factors to consider—and the order in which you need to consider them—to ensure your new warehouse design delivers the results you want.

1. Business Needs

This may seem obvious at first, but in my experience it's not. It's very easy to go to a trade show or see an article about a piece of equipment and start trying to figure out how to get the CFO to approve the budget item. The problem is too often this is done without really thinking through why you need that piece of technology and how it fits into the overall business.

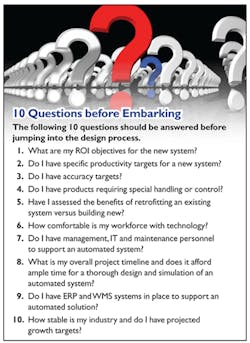

It is best to first take a step back and look at how the business operates today using all the business data you have available. Some questions you should ask:

- What do you do well?

- Where are your weaknesses?

- If you can only afford a partial automation strategy now, what effect will that have on other areas—both upstream and downstream?

- Will that great piece of automation be idle a significant portion of the time because your manual unloading process can't deliver goods to that area fast enough?

- Will it create a bottleneck further down the process by overloading the next station?

2. Building Blocks

After you've determined the business needs today and in the near future, start looking at the building blocks of the system. You want to know what you need to accomplish in the space, and what all the steps in the process are and potentially could be. You don't need to get terribly specific just yet. It's more important to look at what the overall flow should be, based on the business data you accumulated through the questions you answered in the first step.

Think like an architect considering a rough list of materials that might be used in a building (e.g. stone or steel façade). You don't necessarily know how big the blocks will be or how, exactly, they will fit together. But you do need to know which blocks you'll need.

It's the same with warehouse design. You'll probably have an idea of the technologies you plan to install. So then it's a matter of how those technologies or building blocks can be used most effectively based on your business needs.

For example, you might want to see if an automated storage and retrieval system (AS/RS) can be used not only as a workflow buffer into packing, but also for residual handling and to drive the picking process. You might want to determine if you can use unit sortation to support shipping and order consolidation. The objective at this point is to get those building blocks down on paper, then start looking at the different ways you can use them.

You may not get to one final design at this point. In fact, you may have several. You'll then need to start weighing the viability of each design concept based on factors such as the economics (initial capital outlay and the cost to operate that system), the use of space within the warehouse and how the various technologies fit together. In the last case, you may find that the individual technologies you've selected are all good, but don't flow together into a single system the way they should. This is the time to discover all of that, before you start determining your final design.

3. Simulation

Once you have what you believe to be the right design, it's time for simulation. This is a critical step, although some people try to move too quickly through this phase or skip it entirely in a desire to get the new facility up and running.

One of the big reasons running simulations is critical is that the technology used today requires more initial capital outlay than simply hiring humans to do the work. In addition, the further down the design road you go, the more expensive mistakes become. Simulation helps you mitigate risk and validates your design concept.

If you made assumptions in the first two phases that turn out not to be true, or miscalculated in some other way, running a simulation can save you a lot of money in re-work down the road. It also gives you one more opportunity to tweak your designs and try different combinations to achieve the optimal solution rather than one that just works.

A good simulation lets you plug the data you have into the design you've created to see how well the system achieves the stated goals. It then allows you to try different scenarios to see how the system reacts—including testing to see how quickly it recovers from a disaster. By building a working model of the system, you can ensure you have the opportunity to fully evaluate and validate it to remove doubt about whether the system is viable for your needs. If one or more pieces don't work as planned, or the design isn't delivering the results you need to achieve, this is the time to find out—before you've invested a great deal of time and money to put it in place.

During simulation it is essential to begin establishing the requirements for the system controls and software. Incorporating the actual system controls approach in the model should be part of the simulation. This helps you fully understand and develop the software requirements.

One residual effect of having a full working model in place is it can be used to train new personnel later. Another is that if business conditions change in a year or two, you can plug new technologies, system rates, or other data into the existing simulation to see the effects they will have.

Again, a good example is GTP. Moving into GTP can be disruptive to an operation accustomed to working with full case, pallet quantities, or more conventional split-case picking technologies. To effectively manage a system with GTP, you may require a different inventory strategy to match the technology applied. If you have a full simulation in place, you can use it to determine the effect moving into GTP will have on the operation, and the most efficient way to accomplish it with the least disruption. All of this will help you get to market with your new initiatives faster.

4. Integration

Once you're satisfied with the results of the simulation it's time to move into the working layout of the facility. This is where warehouse design ceases to be theoretical and starts becoming practical. Rather than saying you want a sorter here or an AS/RS there, it's time to select the specific technologies and their configuration.

Because you're getting physical, you will also want to involve other engineering teams at this point. These teams can include the mezzanine or structural, mechanical, and electrical groups. Real-life warehouses are rarely as simple and pristine as we would like. There are always obstacles to work around, such as a sprinkler system pipe or a support beam in an inopportune spot, as well as traffic flow and other issues to be considered. You will also need to determine the electrical power, communications and HVAC requirements. You want to allow for all of that in this planning phase since, again, it is less costly to make adjustments on paper than it is in the field. You want to ensure you're using the space you have most effectively and efficiently.

One other aspect that needs to be worked out at this time is the integration of controls. At this point, the software and controls approach has been established during the system simulation. Building upon this evaluation, the final controls requirements can be developed and code development can commence.

Maximizing the value of your investment in warehouse design isn't just about the physical space; it's also about making sure controls are properly integrated to make it easy for personnel to operate a relatively complex system. When you apply all the different software packages, they must work as a single cohesive system, instead of a mish-mash of unrelated applications.

While it seems self-evident, it's not as easy as it sounds. The software for most material handling equipment is designed to be self-contained. Integrating all of the controls together usually takes much longer than most organizations expect. But this customization is critical for delivering the results you seek. Be sure to build it into the plan.

5. Implementation and Training

The final phase, of course, is implementation—taking all the hard work and up-front planning and translating it into an actual warehouse or distribution center. At this point you will be procuring equipment, finalizing the software coding, testing and ensuring everything works the way it should.

While the importance of this phase should not be minimized, by following the first four steps properly there shouldn't be a lot of need for adjustment now. Almost all the kinks should be worked out, allowing you to move quickly through this phase and start realizing the payoff on your investment. You'll also want to start training your personnel on the new system so they're familiar with the equipment and procedures and can hit the ground running the day you cut the ribbon. Again, the work performed during the system simulation can be leveraged to help make personnel training more effective.

Delivering Success

When warehouses were primarily dependent on human beings, there was far more room for error and adjustment in warehouse design. After all, no mechanism is more flexible than people.

With today's emphasis on automation and efficiency, however, that is no longer the case. You have to get it right the first time.

Spend time up-front to be sure the design is right for your business needs, and that everyone is fully trained on the system (including maintenance staff) and knows how to get the most out of it. It may seem like a lot of work at first, but it's the fast track to a successful 21st Century warehouse design.

Clint Lasher has 19 years of experience at Wynright Corporation, centered on design engineering, system sales and business unit leadership – all within the materials handling industry. As president, engineering and integration, Oak Lawn Division, he has advised some of the company's largest clients regarding their systems' needs. He can be reached at [email protected].